Hello. I’m Hishiya, a sushi chef with over 50 years of experience. I’m also the co-founder of REONA Sushi Tokyo, located in Kanda, Tokyo, where I oversee the crucial aspects of sourcing ingredients and the meticulous preparations that precede every sushi service.

Today, the word “Omakase” is recognized and understood across the world, not just in Japan. That brings me great joy—because I was one of the very first sushi chefs to offer omakase as a formal menu item in Tsukiji, a district widely considered one of the birthplaces of Japanese sushi culture, alongside Kanda.

The fact that omakase has captivated so many around the world is still astonishing to me. With the opening of REONA Sushi Tokyo—an establishment devoted to sharing the traditions and techniques of sushi globally—I felt this was the perfect opportunity to share my own understanding and personal experiences with omakase.

In this article, I’ll answer fundamental questions: What exactly is omakase? How did this style emerge? How has it evolved? What are its strengths—and its risks? Finally, I’ll introduce the unique omakase experience we offer at REONA, one designed not just to satisfy but to educate and inspire.

I have served sushi in Tsukiji — the sacred ground of sushi — to a wide range of guests, including world-famous chefs such as Rokusaburo Michiba, the legendary chef known as “The Iron Chef,” as well as gourmets and curious travelers from around the world.

From the very early days, I was among the first to offer Omakase as a formal menu style. That is why I believe I have something meaningful to share.

Omakase is a polite Japanese expression meaning “I’ll leave it to you.”

In the world of sushi, this means a customer entrusts the chef with all decisions: which ingredients to serve, how to prepare them, and in what sequence. It’s inherently a multi-course format, and in Edo-style sushi, it is considered a tasting experience.

From the chef’s perspective, omakase grants full creative control—but also carries immense responsibility. It’s up to us to determine what to serve, how to prepare it, and how to sequence the entire experience. In short, the quality of the omakase course is a direct reflection of the chef’s technique and ingredient sourcing skills.

This is why we sushi chefs work tirelessly to choose the best seasonal ingredients and to prepare each piece in the style we believe will deliver the best possible experience.

Surprisingly, omakase is a relatively new concept within the 200-year history of Edo-style sushi.

It’s said that omakase-style ordering—where the guest leaves all decisions to the chef—only began to appear in Japan about 50 to 60 years ago. Initially, omakase wasn’t a formal menu item. It was an informal agreement between long-time regulars and the chefs they trusted. In other words, omakase wasn’t for everyone—it was a privilege for seasoned patrons who knew how to read the room and the chef. It wasn’t until about 30 to 40 years ago that omakase became widely accepted and printed on menus. I’ll share later how I first introduced it at Tsukiji.

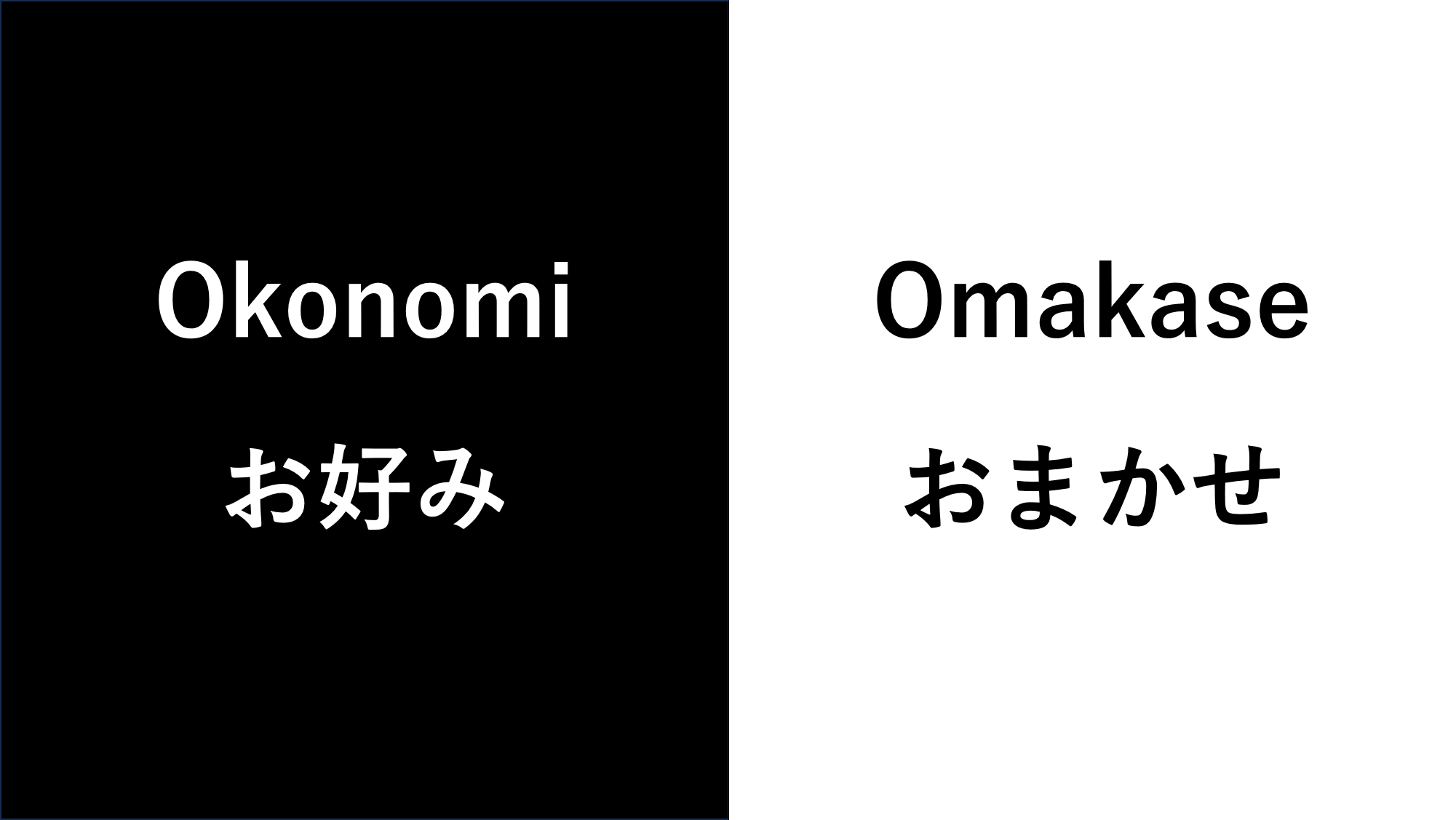

Before omakase gained popularity, most customers used a traditional ordering style called okonomi, meaning “as you like it.” In the early days of sushi, it was closer to fast food. Even into the 1980s, most sushi shops focused on casual service. Customers would drop in, order a few seasonal items, and leave quickly. In that context, a lengthy omakase-style course simply didn’t fit.

Also, Edo-style sushi was far from mainstream at the time—even in Japan. Most customers were already familiar with sushi. They knew which fish were in season and came with specific ideas of what they wanted to eat. So for those diners, okonomi made perfect sense.

But how, then, did omakase come to replace okonomi as the mainstream ordering style? Let me share my personal story.

This was during my time as the head chef and general manager at a famous sushi restaurant in Tsukiji.

Until its relocation in 2018, Tsukiji was home to Tokyo’s largest fish market for over 80 years. It wasn’t the tourist hotspot it is today—it was a working neighborhood, populated by chefs, market workers, and food professionals. There were many sushi restaurants even then, but our customers were industry people: market workers, chefs, vendors, and discerning gourmets who came specifically to taste the best ingredients. They mostly ordered in the okonomi style, carefully choosing what they wanted to eat. Some even knew exactly what each restaurant had purchased that morning at the market.

But there were also a few long-time regulars who sat at the counter without saying a word. Their silence was a signal: “Show me your best today.”

One of them was the legendary Rokusaburo Michiba, the Iron Chef of Japanese cuisine. He was one of my most respected customers. When he sat down, I’d automatically serve him a bottle of beer and begin making sushi. No words exchanged. Just quiet concentration. Sometimes he would eat in silence. Sometimes he would look at a piece and not touch it. That was his way of saying, “You can do better.” I’d remove the piece and present another. It wasn’t humiliating—it was motivating. It drove me to refine my skills, to better understand what excellence meant.

That intense, high-context interaction was the essence of true omakase. It was—and still is—a style that only works when the chef has the skill, intuition, and ingredient knowledge to meet the guest’s trust.

As time passed, Tsukiji began to appear more often in magazines and on TV, gradually attracting tourists and office workers who were unfamiliar with sushi. Many of them didn’t know what was in season, what to order, or in what sequence to eat. The sheer number of sushi toppings made it difficult for beginners to decide.

That’s when I had the idea: what if I adapted the “professional omakase” style for general customers? What if I offered it on the menu, so that even those unfamiliar with sushi could order with confidence?

That’s how “Chef’s Omakase” was born—named after me, the head chef. I was the first to formally present omakase as a menu item at Tsukiji.

The result? A massive success. Our shop was already well regarded, but our sales tripled. By translating the spirit of omakase from a high-pressure professional setting into something accessible and welcoming, we opened the door for more people to fall in love with sushi. After that, many restaurants in Tsukiji also began adding Omakase to their menus and serving it to their guests.

Omakase is an innovation that made sushi more approachable for more people. In this section, I’ll explain the key advantages. After explaining the benefits, I’ll also discuss the potential pitfalls of this style — because no approach is ever perfect.

If you walk into a sushi restaurant for the first time, how do you know what to order? Most people can only list a few toppings they’ve heard of. But do they know what’s in season? Whether the chef has sourced it well? Whether it’s been prepped with care? With omakase, none of that uncertainty exists. The chef selects the finest seasonal ingredients and prepares them in the method they feel most confident in. That’s the clearest and most reliable benefit of omakase: you don’t have to guess. At a good sushi restaurant, you won’t be disappointed.

It’s said there are over 500 ingredients used in sushi. Even the same fish can taste completely different depending on its cut or preparation.

Tuna head meat, for example, is rarely ordered but makes for incredibly flavorful sushi. Scallops can become rich and tender when lightly seared and shredded. But if you don’t know these options exist, you’ll never order them. That’s the limitation of okonomi: it’s confined to what you already know.

Omakase removes that barrier.

At REONA, we let you compare different parts of tuna—akami, chutoro, otoro—each prepared using a different method. We also serve rare fish like nodoguro (blackthroat seaperch), found only in specific regions of Japan, but renowned for its flavor. With omakase, surprises await you—and each one brings you closer to the deeper world of sushi.

In Japanese sushi culture, regular customers often receive better service. That’s natural—familiarity breeds trust.

But for newcomers, it can be hard to establish that rapport on the first visit. With omakase, the relationship starts smoothly. A pre-designed course allows the chef to focus on execution, while leaving room for conversation. That dialogue builds trust over time. Most sushi chefs in Japan don’t speak English, so for international visitors, that barrier is even higher. But with omakase, even if you can’t talk, you can still enjoy a well-curated, consistent experience.

At REONA, we go further—we have English-speaking staff who help bridge the gap between guest and chef, ensuring a smooth, enriching visit for everyone.

As omakase became more popular, some veteran chefs and restaurant owners began to express concern. And they weren’t wrong. The format has immense value—but when misused, it can produce poor outcomes. At REONA, we’re aware of these pitfalls, and we train our staff rigorously to avoid them.

A good sushi chef constantly improves the omakase course—refining dishes, exploring new ideas, and striving for excellence.

But for less committed chefs, omakase can become a shortcut. Some use it as an excuse to serve only what’s easy or familiar, without creativity or care. Over time, that dulls their skill and passion. It turns omakase into a static, uninspired set menu.

In the okonomi era, chefs had to respond to requests. Each guest presented a new challenge: different preferences, different moods. That dynamic kept chefs sharp. I’ve heard people say, “The rise of omakase created too many lazy sushi chefs.” In some cases, I believe that’s true.

This issue goes beyond individual chefs. Some restaurants misuse omakase as a tool to maximize profits.

They build their menus with low-cost or surplus ingredients, focusing on margin instead of quality. They don’t invest in good sourcing. They don’t train their staff. They don’t prep ingredients with care. That’s unfortunate—but it happens.

Worse, it’s hard for customers to identify such restaurants in advance. If you don’t already know a trustworthy sushi chef, your best bet is to read online reviews carefully—not just star ratings, but actual comments about the fish, the service, and the experience.

I’ve shared the origins, benefits, and risks of omakase. Now let me introduce how we do it at REONA.

We don’t just serve omakase. We use it to teach. Our course is designed as an experience in “understanding sushi.” To our knowledge, REONA is the first restaurant in Japan to offer omakase with education at its core.

I’m nearly 70 now, and after decades of promoting omakase in Tsukiji, I’m once again collaborating with a younger generation of chefs to reinvent it.

To add depth and structure, I partnered with the founder of MagicalTrip, Japan’s largest tour platform, to build an omakase experience that’s interactive, engaging, and informative.

Please check our plan to explore the features of REONA’s omakase program.

Japan has many incredible sushi restaurants, each with its own character. If you’re traveling here, I encourage you to explore widely.

But I also encourage you to start with our Omakase Experience at REONA Sushi Tokyo. Our omakase will help you understand sushi—its foundations, its traditions, and the mindset of the chefs who make it.

Armed with that knowledge, you’ll appreciate every future sushi experience even more. Our goal isn’t just to be the best restaurant—it’s to help you enjoy sushi more deeply. Few places explain sushi in detail. Even fewer do it in English.

We want our omakase to be your first step into the world of sushi — and a memory you’ll never forget. We look forward to welcoming you.